By Catherine Komp,

NC Local Newsletter Editor

Who in state government is a champion of transparency and who has something to hide? We may learn those answers following last week’s 11th hour insertion of provisions in the state budget bill that drastically change the public’s right to information about the state lawmakers they put in office (as well as the ones they vote out).

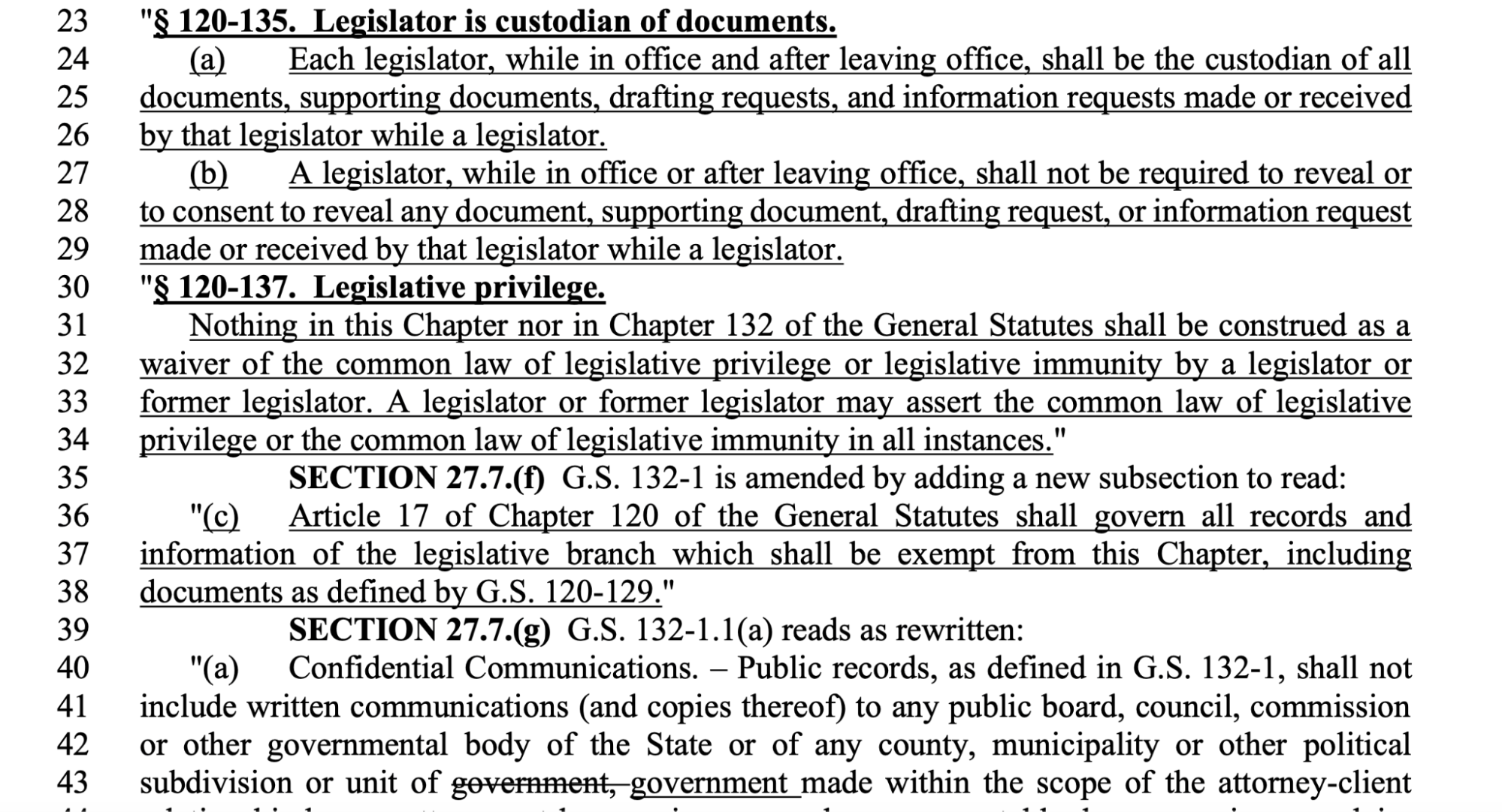

A slate of changes to Section 27.7 (pages 529-530 in the 600+ page budget bill) gives lawmakers the power to determine what to release to the public, what to destroy and even what to sell. Another rollback repeals the law that gave the public access to redistricting information after maps are approved.

Journalists and public information advocates were quick to condemn the changes, which are on their way to becoming law.

- NCPA Executive Director Phil Lucey told NC Local they “aim to turn back this unprecedented and unjustified attempt to change the public’s right to know in North Carolina.”

- In a letter to Senator Berger and Speaker Moore ahead of the vote, the NCBA said the changes will permit the GA to “operate in secrecy, shielded from public view and accountability.”

- In a newsletter with the subject line “I am gobsmacked!”, Carolina Public Press Executive Director Angie Newsome called the rollbacks a “staggering blow to democracy.”

- The coalition American Oversight, which includes the ACLU of NC and the Brennan Center for Justice, as well as the conservative John Locke Foundation also condemned the provisions, with the latter writing: “Rather than restricting North Carolinians’ right to know what their government is up to, the General Assembly should consider strengthening that right by adding a public records provision in the state constitution.”

And a basic, but key fact, comes to mind for UNC Journalism Professor Ryan Thornburg: for decades NC legislators have been subject to public records law just like all parts of government [emphasis mine].

“I’ve never seen any way in which this transparency has hindered their ability to do what they think is best for North Carolinians,” Thornburg told NC Local. “And I haven’t heard any compelling argument that something has happened that requires legislators to be less accountable to the public than they have been in a generation. I haven’t heard any compelling reason that they need to be less accountable or less transparent than the thousands of town council members, county commissioners and school boards across the state.”

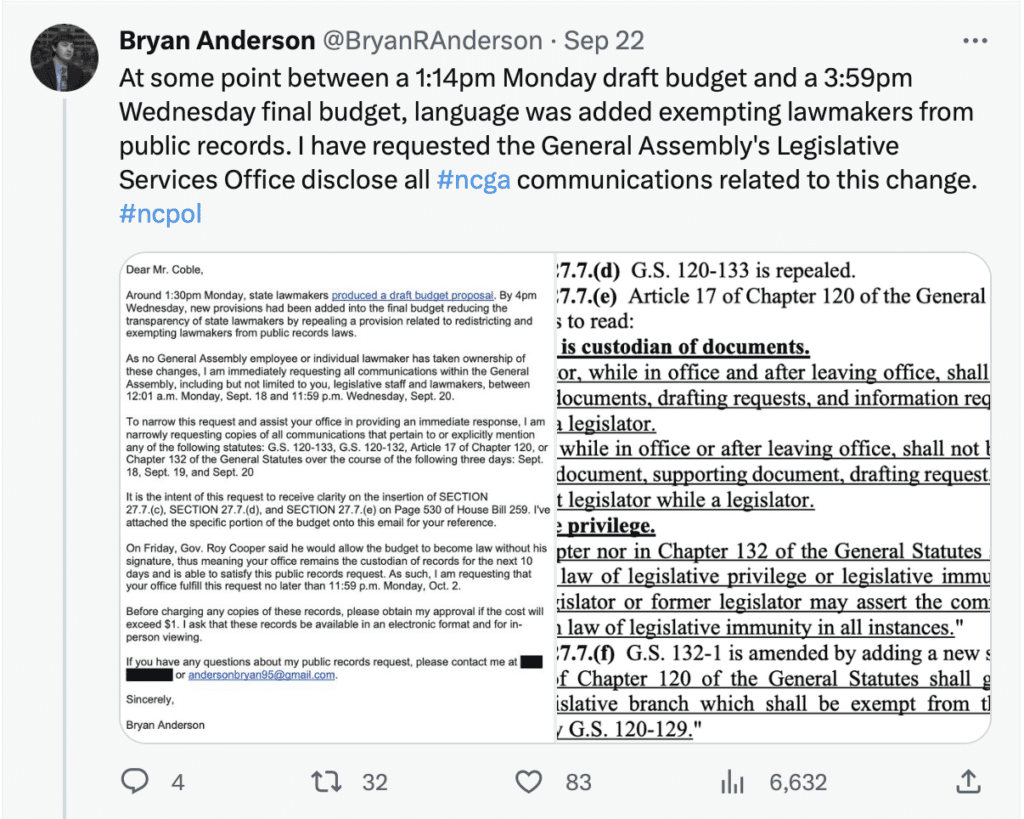

We don’t know who inserted these provisions into the budget sometime between last Monday afternoon when the draft was obtained, and last Wednesday afternoon when the final budget was released. Ahead of the budget becoming law, Journalist Bryan Anderson submitted a records request last Friday to try to find out.

To help break down what we know about the changes and provide some historical context about public records and the GA, I called up Brooks Fuller, director of the North Carolina Open Government Coalition and assistant professor of journalism at Elon University.

CK: What are the biggest changes to public records law?

BF: We kind of have to start at the end of the changes as they’re listed in the document and work our way backward. There’s a section that’s 27.7 (f) (see page 530). The first big change is that instead of applying the public records law to records and information of the legislative branch, all of that now gets funneled through a different section in the General Statute, which is Chapter 120, that’s the large chapter of the general statutes that covers all manner of things involving the legislature.

And then what it does is it says that legislators are now going to be the custodians of their documents, each legislator individually, and they also have pretty broad authority or discretion to determine when they reveal documents, supporting documents and other listed types of records and it gives them a broad, sweeping privilege over when and how they release records that they create during their public service.

They now have something that’s called legislative privilege, where they exercise a great deal of power to determine whether a document should be released to the public or should be kept in secret because it relates to their confidential legislative activity. And it basically says there’s nothing that the public can do to compel them to reveal records of their legislative activity and it defines those records very broadly. So it essentially gives them full decision making power over what records wind up being public.

Whereas before, was it the Legislative Services Office that made that determination?

So not really. In fact, there’s an old attorney general opinion that has said for over a decade that individual legislators are the custodians of those records. But they didn’t have the power to decide whether to give records over or not. They had to obey the public records law. They had to comply. And now it gives them discretion over defining which records they’re going to release. In practice, the Legislative Services Office has been the clearing house for a lot of public records requests, even though there’s nothing in the law that says that they have that authority or responsibility.

The way the law works is that the individual legislator with custody and control of the records can be asked for those records and has to give them over. Now they can still do that, but they have a lot more authority to decide what’s even a public record in the first place, and that’s probably the biggest change.

So in practice, what do the changes mean for journalists and the public?

One of the changes has made all of the redistricting documents like draft maps and draft legislation and communications around redistricting— it’s made those secret as well. One of the essential ingredients about the voting processes in North Carolina is how our maps are drawn and what gerrymanders look like and who the map makers are targeting to get into a district or out of a district and whose districts they’re trying to help, or whose districts they’re trying to maybe harm or eliminate. And all of that information about how those maps come into being— that’s now out of public view. It was already kind of a secretive process during the map making, but at least on the back end, we had the ability to reverse engineer how a legislative mapper, an electoral map, comes into being. And now we don’t even have that. So we lose the history of the maps, we lose the ability to critique or comment on the process as it’s taken shape.

I think more than anything, the changes rip power from the public to learn more about the process and to engage. And frankly, as a voter, that can be pretty exhausting. When you feel like you don’t have the ability to participate, I can see how folks would want to throw up their hands and go home if they don’t have an opportunity.

One of the things that this whole package of legislation does is it removes one of the levers of power from the public that we still had, which was our transparency laws. We don’t have an army of lawyers to go to court all the time. We don’t have lobbyists that we pay handsome amounts of money to go put pressure on legislators. What we had was our ability to request information and when that information wasn’t given to us, we then had the ability, maybe in rare occasions, to file a lawsuit to force compliance. Now that’s gone. Like those lawsuits are going to be either far more difficult or they’re going to be dead on arrival and courts are going to be able to side with the legislature much more easily than they maybe had in the past.

To help understand the impact of this, say somebody wanted to look into some of these casino negotiations that unraveled during the last weeks of the budget negotiations. Or someone wanted to find out who put these public records provisions in the budget. Could they get those records, after the budget becomes law?

So a lot of those things, they probably couldn’t get in the first place. There’s actually a really strong shield around when a legislator makes a drafting request or an information request to their staff during the process of drafting a bill. And as part of the process your staff gets information, collects records from out in the public sphere to basically give the legislator an idea of what policy they want to draft and then offer up on the floor. That was always shielded by the Public Records Act. You were never allowed to get those drafting requests or informational requests.

What you could get was things like constituent communications to an elected representative that gave you an idea of what the public was asking the legislator to do and emails back to constituents, what they were telling the people who voted for them. And then in many cases what they were telling each other and if they were communicating with members of an executive branch, those communications, if they were in writing, those could be public too.

So there were actually a lot of things that you couldn’t get so legislators were allowed to make requests of their staff without fear of public records opening up some of those sensitive details about their thought processes about legislation. But you could still get all these other communications about how they conduct public business as elected representatives.

Any other comments on this or what NC Open Gov might be doing related to this?

Nothing to comment on about the near term. We stand to field calls and to help people strategize like we always do. If there are journalists that want to chat with us about what this means for their newsrooms or their freelance work, we want to talk to you, we want to help you. We want to help by also building out your network of getting information from other journalists who are willing to partner with you and share with you and form teams to do the reporting that is going to be a little bit harder now. We act as a hub for those types of conversations.

We don’t litigate cases, so we don’t employ a lawyer to fight in the courtrooms and that’s something folks have asked us if we’re going to do. But that’s not something that we do anyway, we’ve never done that. But we are going to assist the folks who are trying to figure out how to chart the course.

Get in touch with the NC Open Government Coalition here.

UNC’s Thornburg makes another compelling case for why all news organizations should be invested in this issue — it affects your bottom lines. He told NC Local he can’t think of any public policy more important to the business side of doing journalism than public records.

“News organizations should make public records their top legislative priority,” said Thornburg. “Since 1995, this state’s once remarkably accountable public records law has been eroded bit-by-bit in ways that are often obscured from public view. Without pushback, journalists in North Carolina will find themselves facing rising costs of gathering the news and creating their products. This is a business imperative.”

If your news or information organization is working on this issue or has questions, get in touch at nclocal@elon.edu