By Catherine Komp,

NC Local Newsletter Editor

Medill’s Local News Initiative at Northwestern University describes their annual State of Local News report as an “MRI” of the health of local news and it’s long been a go-to resource to understand the growing crisis of “news deserts.” As expected, 2023’s report shares more alarming statistics about the diminishing presence of local news across the country. This year, they’ve added a new layer of analysis — predictive modeling.

“This predictive modeling paints a sobering picture,” writes Medill Local News Initiative Director Tim Franklin. “There are 204 counties that currently are news deserts, with no newspapers, local digital sites, public radio newsrooms or ethnic publications. But in studying the characteristics of current news deserts, Medill experts have identified another 228 counties at substantial risk of becoming news deserts in coming years. Why is that important? It gives community leaders, philanthropists, industry executives and journalists an opportunity to act before an area becomes a news desert.”

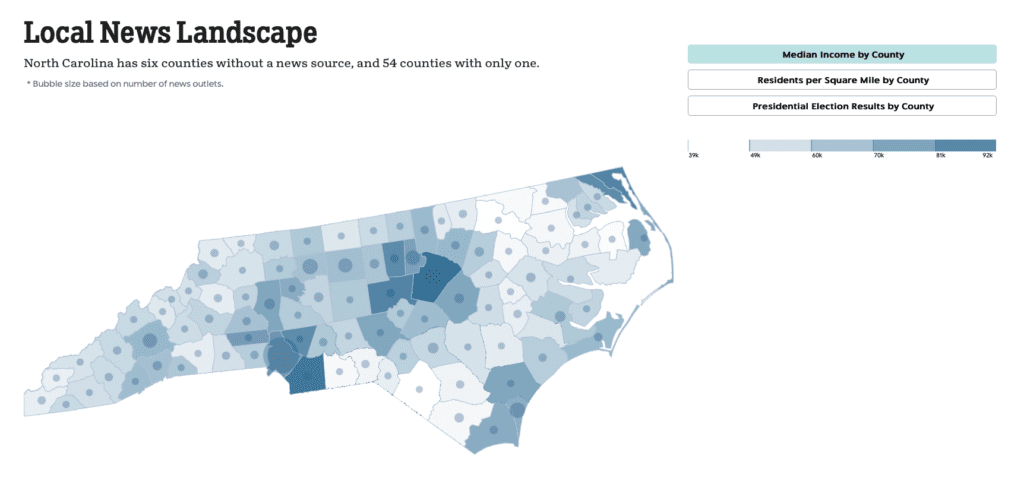

The 2023 State of Local News report is based on data from more than 9,000 news organizations across the country. There are 400+ interactive maps which let you explore down to the county level the presence or absence of news providers in addition to data about median income, population and presidential election results.

This is also the final State of Local News report to be led by Penny Abernathy, who started this work 15 years ago and launched the annual report while serving as Knight Chair of Journalism at UNC. Abernathy’s years of meticulous research and vision for solutions helped turn the issue of news deserts into an urgent, national conversation.

Another accomplished news researcher, Sarah Stonbely, took the helm as Director of Medill’s State of Local News Project in September. (Check out her extensive local news research for the Center for Cooperative Media.) We have a Q&A with Sarah below, but first a few highlights:

National State of Local News 2023

🗞️ About 6,000 newspapers exist today, down from about 24,000 at the beginning of the 20th Century.

🏘️ Most communities that lose a newspaper do not get a replacement — either print, digital or broadcast.

🌐 52 million residents live in about 1500 counties with only a single source of local news

❌ 3 million people live in 204 counties with no news outlets.

📍More than a quarter of community-based ethnic news outlets have closed in the last three years, leaving only 723 still actively producing news.

📻 There are about 400 public radio stations, but only 213 are currently producing original journalism.

📻 Out of 158 public tv stations, only a third have at least one reporter on staff. Only nine stations produce a local news show that airs at least three days a week.

💻 There are about 541 digital news outlets but more than 80% are located in large, metro areas.

📉 There is high turnover with hyper-local, for profit news sites: while researchers added 53 new digital sites over the past two years, they removed 39 inactive sites.

North Carolina State of Local News 2023

📍NC has 206 news outlets, including 155 newspapers, 15 digital sites, 29 ethnic outlets and 7 public broadcasting organizations.

🗞️ NC has 43 daily newspapers and 112 weekly

📱 NC’s digital outlets include 8 for-profits and 7 non-profits.

🌐 NC’s has 10 media outlets serving the Black community and 19 serving the Hispanic community.

📉 NC has 6 counties without a news source, and 54 counties with only 1.

NC Local: What attracted you to local news research?

Sarah Stonbely: I started out studying national news, but over the years it became clear that local was really where the crisis was going to be. I was then able to serve as research director at the Center for Cooperative Media in New Jersey, which has an intensely local focus, and saw up close the struggle and also the impact that good local journalism can have.

NC Local: In the intro, Medill Local News initiative Director TIm Franklin describes the 2023 report as “the most extensive yet.” What’s new this year and how do the additions help us better understand the local news landscape?

Sarah Stonbely: This year, in addition to looking at newspapers, digital-first, and public broadcasting, we revisited the ethnic media outlets that we’d cataloged in 2020, to see how they’d fared the pandemic. We found that more than a quarter had closed, largely due to the loss of small businesses in ethnic communities that had provided funding through advertising. We also added a more detailed look at public broadcasting across the country.

We also added a new “Bright Spots” map, which shows all of the startups since 2005, as well as 17 featured outlets of all kinds that have promising business models.

Finally, we also added this year a Watch List map and a Barometer map, both of which show counties that have the bare minimum in local news provision and are at risk of becoming news deserts, based on demographics that mirror current news deserts.

NC Local: This year’s report has good news and bad news. Let’s start with the latter and the continued loss of newspapers, ticking up to two-and-a-half a week in 2023 or about 131 newspapers in 77 counties. Where are we seeing the biggest losses?

Sarah Stonbely: The biggest losses are in rural and poor counties, which have always been underserved and are even more so now, deepening the divide between journalism haves and have-nots in this country.

NC Local: Along with this, the number of journalists has dropped significantly: about 60% of newspaper journalists — 43,140 — have left the business since 2005. Locally here in North Carolina, the decrease is about 55% since 2005. What impacts do you see from these losses?

Sarah Stonbely: These losses are devastating. There are fewer eyes on the people in power, and fewer people to tell the stories that bring communities together and help fulfill our democratic mandates. When a journalist loses their job, often all of the institutional knowledge they’ve amassed is also lost, and the community and country are worse off for it.

NC Local: Are you seeing anything else on the horizon for North Carolina in terms of what’s at risk or areas on the “Watch List” and “Local News Ecosystem Barometer?”

Sarah Stonbely: Like a lot of states, North Carolina has a lot of poor and rural communities, and those communities are most at risk of becoming news deserts – especially in the northeast of the state.

NC Local: The report also tracks digital news sites, which the team has found is hovering around 550, most near larger cities. Outside of better broadband access, what’s preventing the expansion of digital news to more communities that lack local news?

Sarah Stonbely: Lack of broadband is a big impediment, but there are two other variables that make it really difficult for digital sites to be sustainable: the lack of a strong retail base in a community, which could provide advertising; and low median household income, which makes it less likely that the community can sustain an outlet through audience revenue.

NC Local: New this year is tracking public broadcasting — but it seems as though community stations and low power FM, which in many cases do provide local news and information, are not included. Why were these left out, and are there discussions to broaden the database in future reports?

Sarah Stonbely: We’re always looking for ways to supplement and build on the data, and having community and low-power FM stations would be awesome! Unfortunately they’re really difficult to identify and track, because they fly under the radar of any national organization that tracks things like that (but if you have any ideas please do let me know!).

NC Local: You’re also tracking “ethnic” media – which the report points out include some of the oldest newspapers in the country as well as newer, innovative approaches like serving communities on WhatsApp. How did the team decide what to include in this year’s report?

Sarah Stonbely: A good place to look is our methodology section, where we lay out how we decide what to include. One of our big goals for the 2024 report is to provide a more comprehensive look at ethnic media, and to add social media.

NC Local: On to the “good news” of this year’s report, which includes “Bright Spots” — an interactive map highlighting local news startups, including a number here in NC along with interviews and case studies. How did you determine what to include in this map and what are some lessons learned from these local news organizations?

Sarah Stonbely: There were long conversations about which outlets to feature, and the overarching goal was to show diversity in terms of medium, geography, and business model. There are so many lessons to learn from the orgs we feature! One of the takeaways is that publishers who think outside the box can be really successful if they base their business model on the community they’re trying to serve. Another is that there is no one solution, it’s going to have to be a wide range of things.

NC Local: There is a lot of excitement as well as pragmatism about the Press Forward $500 million investment in local news. But your report points out that even with additional contributions from local funders, it doesn’t replace the tens of billions in ad revenue lost in the last two decades. State and federal policy proposals would provide some revenue, but that still doesn’t seem to be enough. What else is needed to adequately fund local news?

Sarah Stonbely: It’s a good question. I’d say again that it’s going to need to be a number of things: philanthropy, a recognition that people are going to have to pay for quality local journalism (audience revenue), and that it’s something that every community needs. It’s going to be about public policy to support local news orgs, and maybe at some point taking some of the power away from the platforms (Google, Facebook) that make it so hard for digital journalism to be profitable.

NC Local: The State of Local News is designed for journalists, media leaders, policy makers, philanthropists and scholars. But what about community members? Do you have suggestions about how news and information providers should share this with their audiences?

Sarah Stonbely: I love this suggestion; yes, the public needs to be made aware of the crisis for local news, as well as the solutions that are pointing the way forward. Coverage such as yours are a great step in that direction. We can also think more about how to make this research more widely accessible!

NC Local: Your colleague Penny Abernathy started this work 15 years ago and is wrapping up her role with the State of Local News. What impact do you think she’s had on our understanding of the problem and efforts to course-correct?

Sarah Stonbely: Penny Abernathy is a force, and has had such an important role in bringing this issue to the forefront; it’s almost impossible to overstate how important the annual State of Local News reports have been to the national conversation about this topic. I’m honored and humbled to be able to work with her and to eventually lead this effort forward.

The Local News Initiative is rolling out additional sections of the report in the coming weeks, including in-depth examinations of serving rural and metropolitan audiences; the increased attention about public support of local news and strategies to revive local news. The Initiative will publish a full report in 2024, and plans to launch a new quarterly newsletter to share updates on data, developments in the field, and spotlight solutions to sustainable local journalism.

Have additions, corrections or recommendations for the State of Local News? Get in touch at stateoflocalnews@northwestern.edu.