By Catherine Komp, Engagement Director

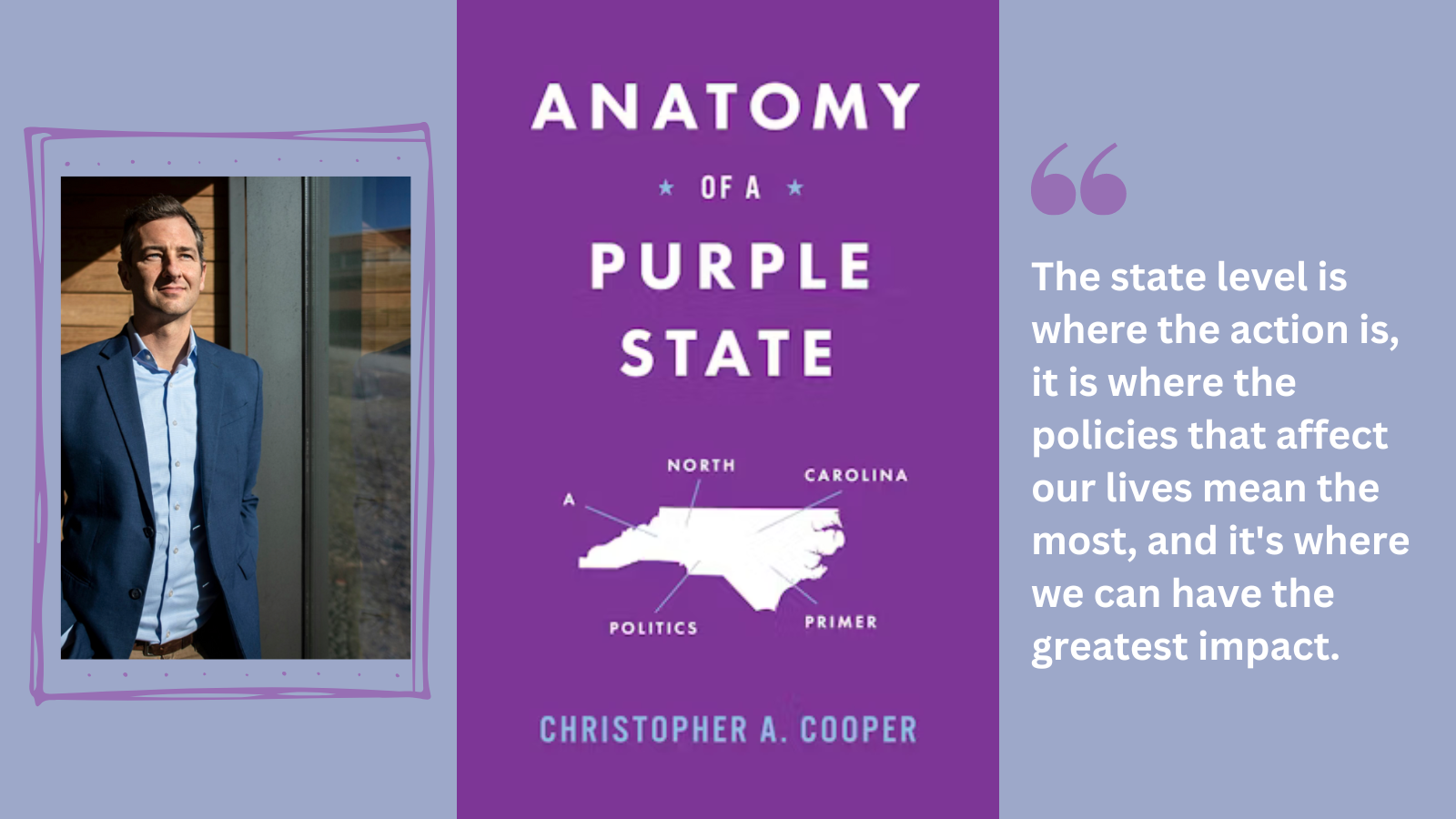

In the acknowledgements of “Anatomy of a Purple State: a North Carolina Politics Primer,” Political Scientist and WCU Professor Christopher Cooper writes “answers are easy to come by, the thought is in the question.”

“I think of this adage a few times a week when the phone rings and there’s a journalist on the other end of the line who asks questions that cause me to think about North Carolina politics in new ways,” wrote Cooper.

Available now for pre-order and officially published October 15, “Anatomy of a Purple State” is based on years of conversations, research, writing and reflection, as well as Cooper’s passion for helping more people understand NC politics and the role they can play in shaping it.

“I have no illusion that people are going to remember every fact or story from this book, but I do hope that it helps reorient our focus to the state level, because it is where the action is, it is where the policies that affect our lives mean the most, and it’s where we can have the greatest impact,” Cooper told NC Local.

It’s not a long read, 148 pages and that is by design. Cooper wanted a book that was accessible to new and seasoned journalists; educators and students; people elected to office and those thinking about running for the first time and, importantly, anyone who wants to become a more active and engaged participant in North Carolina politics.

While Cooper points out that each section could be a chapter and each chapter an entire book, he weaves together just the right amount of historical context, data (distilled from 100+ spreadsheets!) and interviews to give readers a good grasp on everything from constitutional amendments and racial and gender representation in the General Assembly, to the rural realignment, gerrymandering, and the rise of the unaffiliated voter. Cooper explains structural shortcomings and demonstrates where and how North Carolina is an outlier among other states. He wraps things up with a starting point for reform and five concrete steps that could be taken to put North Carolina on a path to better governance.

We had the opportunity to chat with Chris about “Anatomy of a Purple State,” which he offers a definition of in the book (it’s not synonymous with “swing”) as well as plenty of ideas for topics and angles about NC politics that could be explored further. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

NC Local: Let’s start with the origin story. Could you share what sparked the idea for Anatomy of a Purple State?

Chris Cooper: I’d been bouncing around a few ideas I had for books for a while and then I had a conversation with WUNC’s Jeff Tiberii when he was early on in his time covering state level politics. He was asking me about what he should read and I had gotten questions like that before, but it was the first time where I really thought, well, maybe we need something updated.

There’s a couple of books that I’m sure folks are familiar with, Paul Luebke’s Tar Heel Politics and Tar Heel Politics 2000, which came out in 1998 so it’s been a minute. Rob Christensen had The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics that came out in 2008. This is before the Republican takeover. There’s been some great books about parts of North County politics since then. Tom Eamon had a really good historical look, The Making of a Southern Democracy, and there’s Fragile Democracy, a great book about voting rights in North Carolina.

But there just wasn’t anything really updated where I could say, “Hey Jeff, here’s what you should read.” And I kept hearing from more journalists who are new to the state or national journalists who would come down and try to get up to speed on North Carolina quickly. So I thought I would try to write something that was hopefully somewhat readable and engaging and would give folks a sense of where our politics are today.

You talk regularly with a lot of journalists, and you recognize them in your acknowledgements, writing: “Answers are easy to come by, the thought is in the question.” What are some examples of how NC’s journalists have helped you think about politics in new ways?

I’m a much better observer of our state’s politics because of the questions that people ask. Just this week somebody was asking me to look a little bit into what the down ballot effects of Mark Robinson might be. In other words, how many of these districts might swing in one direction or the other based on Mark Robinson’s poll numbers and what Mark Robinson’s performance might mean in the ballot box. I’d been sort of bouncing around an idea like that, but I wouldn’t have made the time to do it and now I am and now I will.

In Jackson County, there is a woman who is running for a county commission seat in a district and she had filed and everything was fine and she won the primary. And then it went to the general election and all of a sudden it was discovered that she actually lives in a different district; that her house abuts the district she had declared for but she hadn’t lived there. And so that sent me down a long rabbit hole of trying to understand residency requirements and what it really means to live somewhere.

Those are two very concrete examples. But I would say in general the quality of the questions that people ask. The other thing I’ve learned a lot about from the journalists in this state is the need to put people in stories. That seems obvious from a journalistic perspective, but from a social scientist that isn’t always the obvious gear to go to. And so I tried in this book to make sure that we had voices of real people and we had voices who could tell us the experience, for example, of being a state legislator or being a lobbyist, and to center stories around people and then let the data fill it out. Before I had the benefit of talking to so many smarter journalists, I would have approached the problem in the opposite direction.

I did love the personal interviews you included, especially Lindsey Prather, I learned so much about what it’s like being a woman in the GA. We’ll get to that in a minute, as you have a chapter on underrepresented groups. But first, Chapter 1. You lay some context and answers to a question I’ve had since moving here: why and how so many significant policy decisions seem to be made in such haste and without regard to public input. You lay out some clear answers to this in the book, competitiveness & winner takes all politics. And I’m wondering in an environment where it seems like compromise rarely happens, what’s the impact on the public?

I think the impact on the public is that they largely tune it out. They largely tune out state politics. To some degree they just feel like there’s not much happening there, that there is not much compromise. They’re right certainly on the latter. I think they might be wrong on the former, although I understand where the perspective comes from. But yeah, I think the public is not cluing into state politics.

So I have no illusion that people are going to remember every fact or story from this book, but I do hope that it helps reorient our focus to the state level, because it is where the action is, it is where the policies that affect our lives mean the most, and it’s where we can have the greatest impact. These are people you can get in touch with. I can send a text or a phone call to a Republican or a Democratic member of the General Assembly and my odds of getting a response are decent. If I try to send it to people in Congress, my odds of getting a response would run zero. So there’s an access benefit as well as an impact benefit.

I was fascinated by your research into all the constitutional changes and amendments that have happened over time, it was a pretty frequent thing for a while. What do you think would be needed to revisit the Constitution in the coming years, and in a way that benefits good governance?

I think it’s going to be really difficult. And it’s a conversation that I think we should be having. We’ve had three constitutions in the state of North Carolina, and there is nothing that says that these were the laws handed down by Moses on stone tablets, right? We can change these and that to me is the central point I hope people come away with— that it doesn’t have to be this way. It’s going to be difficult for wholesale changes, but I think we can chip away at a few things.

In the conclusion I talked some about the literacy test, which remains in our Constitution. There’s absolutely no reason that it should be there. We’ve got John Locke Foundation on the right, we’ve got every left-leaning person, we have Phil Berger, powerful Republicans, powerful Democrats all think that we should get rid of this thing. There’s a lot of reasons why maybe we haven’t, but one thing I’ve heard is that it’s just symbolic, we don’t use the literacy test anymore. And that is true as long as Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act remains, and considering some of the recent court decisions we’ve had in South Carolina and Alabama, I don’t think we should assume that Section 2 will be here in perpetuity. It is a symbolic issue that can become a very real issue. So I think there’s some little things like that that we can do to the state constitution through some of these constitutional amendments. We don’t have referenda, we don’t have initiatives in the state. It’s the one place where the people can vote directly on the issues.

Why don’t we have initiatives or referendums and what could be done to change that?

I’ll take the last question first, that’s the easiest. That would be a constitutional amendment. The reason we don’t have them, most southern states don’t. Referenda and initiatives tend to be in Western states. Although that’s not entirely true as we saw in Kansas with their abortion initiative a few years ago. But it would take the General Assembly giving power directly to the people to take an idea, get petitions and pass something into law.

Unfortunately, especially with people’s inattention to state politics, I think that the odds of that are very, very low. The one way it could happen is if people did pay more attention to state politics. If they paid more attention to the General Assembly, if they held people responsible for their actions positively and negatively. But until that day comes, I don’t think we’re going to get it because it would be them giving away power.

You also look at the racial and gender makeup of the General Assembly, laying out some of the important historical context, like the 30 African Americans elected to the GA between the end of the Civil War and 1876; and Lillian Exum Clement’s election to the House in 1921, before women had the right to vote. Then you weave in contemporary policies, data and some personal narratives to demonstrate today’s GA, which is still lacking in diverse representation. What are the factors contributing to this, and how could news and information organizations play a role in shining more light on this topic?

There are structural factors at play here. For example, when we quit having multimember districts in the state of North Carolina, we saw a massive increase in African American representation, so that was a structural and institutional change that we made as a state (in response to some legal issues) that increased African American representation.

Other institutional factors for women, for example, would be the lack of professionalism in the General Assembly. We know that in these less professional legislatures, in other words ones where we pay less money, have less staff and have shorter session lengths, you’re less likely to get women to run for office.

I wish I had read more about Asheville City Council and Durham County Commissions becoming 100% female. It was a major moment. It happened at the same time and it was to the best of my knowledge, the very first all female city council and the very first all female county commission in the state of North Carolina. To me that was a golden opportunity for people to write about the problems of female representation and the promise of female representation and what difference it has made and what difference it makes in how people perceive their government. We know that, not surprisingly, when women see women in office, they tend to trust government more. They also tend to think it’s a path that maybe they would want to take someday. So there’s real downstream effects in time for having a more representative body.

There’s been this other pattern in terms of female representation that I tried to identify in the book.It wasn’t that long ago that Democrats and Republicans in the General Assembly had about the same number or the same proportion of women. In other words, Democrats did not have more gender diversity than Republicans. That’s a totally different world now. The Democratic delegation in Raleigh has become much more diverse over time and the Republican delegation has become much less diverse over time. And that’s happened at a time where the Republicans are gaining seats. So you put all that together and what it means is that we’re not making much progress in terms of female representation.

With the continuing need for more representation by people of color and women in elected office, both the General Assembly and our local offices, which issues aren’t rising up on the priority list or aren’t aren’t getting as much attention?

We know that women tend to promote different kinds of policies than men do, and that people of color tend to promote different kinds of policies than whites do, even if they’re from the same party, which makes sense, right? Your background, whether race or gender or what you do in your spare time matters. We know that people who smoke vote differently on tobacco policies. We know that people who have children vote differently on childcare issues, whether men or women, so it just makes sense that your life experience matters.

By not having as many women in the General Assembly and on county commissions and city councils and in our congressional delegation, what we see is that issues around health care tend to get less attention. Childcare, not that all women necessarily have children or experience childcare problems, but there is a sensitivity to those issues that you tend to see among female legislators, regardless of whether they had children or not. And then, what we know from all sorts of organizations, which is that organizations work differently and better if you have more diverse coalitions of people within them.

It is often viewed through a partisan lens because of the way various groups tend to vote, but this should be a nonpartisan outcome: to have better female representation. The easiest way to increase female representation in the General Assembly would be if the Republican Party had more women running for office, so it is very much a bipartisan problem with bipartisan solutions.

North Carolina has a lot of rural communities and you bring forward some really interesting data about that as well as talking about this concept of “rural realignment.” What do you think is important for people to understand about rural parts of North Carolina?

The reality that we all take for granted now that urban places are blue and that rural places are red is relatively recent in North Carolina political history. Until the 1990s, it was actually the rural places that tended to have more registered Democrats than the urban places. And as recently as 2000, Buncombe County and Mecklenburg County, not exactly known as conservative stalwarts today, voted for George W. Bush, the Republican candidate for President. So the last true realignment in the South was these rural voters to the Republican Party.

I also want people to know that it matters, that we have the second most rural voters in this country after Texas and that it is not simply enough to run up the score in urban areas for any candidate to win. It’s not Georgia. This has been covered by many national media: Atlanta dominates Georgia. No two or even three cities dominate North Carolina, so you have to pay attention to the rural vote.

That also makes our elections more expensive, and it’s harder to run as a candidate. Not that we need to feel terrible for politicians, but to think through what that means if you’re running for state auditor, you don’t exactly have tens of millions of dollars in your campaign account. If you’re running the same campaign in Georgia, maybe you focused in Atlanta and Savannah and Macon. In North Carolina, you do have to go from Murphy to Manteo, and you do have to spend time in rural areas and that costs money and more importantly, that costs time.

You highlight a very historic day in North Carolina history, September 12th, 2017 and it happened with barely a murmur. What was this and what was the missed opportunity?

That’s the day where unaffiliated crossed Republican to become the second largest registered group in North Carolina politics and then just last year, unaffiliated crossed Democrat to become the largest group in North County politics. People didn’t really take note of it in 2017. I think NC Insider had a little blurb that quoted a tweet by Michael Bitzer, and that was about the size of it.

It was incredibly important. I think the voters were trying to signal something to us and we weren’t listening. And I think one reason we weren’t listening, is that we give an awful lot of our collective head space to political consultants whose job it is to win the next election, not to think about the long term health of democracy. If you only care about winning the next election, then it doesn’t matter if these people are registering unaffiliated, all that matters is how they’re going to vote.

But if you’re concerned about the long term health of democracy and if you buy that you need two people to run for every office to have some choice, and if you buy, as I demonstrate in one of the chapters, that you pretty much have to be in one of the two major parties to win, then we’re creating a real problem for democracy in North Carolina 20 and 30 years from now. If all of my students are registered as unaffiliated, that’s basically saying they can’t run for office, and so a smaller and smaller group of people are going to be making decisions about who runs for office and ultimately the ones who make decisions over our lives.

You outline some of the really inequitable realities for people that want to run as unaffiliated candidates. So what would it take to help level the playing field for them in terms of getting on the ballot?

To understand how hard it is, my favorite example is Transylvania County. We had three Republicans on the County Commission, they won and they decided they weren’t wild about Donald Trump and so they decided to change to unaffiliated and assumed they’d be reelected. All three were promptly voted out of office. We have Shelane Etchison running right now as an unaffiliated candidate for Congress. We created the unaffiliated category in 1978. It’s been until 2024 that we have one person qualified to run for Congress with this designation. I think it just shows how hard it is. (Editor’s note: NC requires unaffiliated candidates to get what can amount to tens of thousands of signatures to appear on a ballot, while major party candidates only need to pay a filing fee. Cooper’s book has much more detail on this & the rise of the unaffiliated voter, but you can also review candidate requirements here.)

So, what would it take? One, it would take thinking about the structures. We have big battles right now over our boards of elections in North Carolina; the party of the governor gets the chair, the two major parties split [the other seats]. Right now because Roy Cooper is our Governor, three Democrats and two Republicans on all 100 county election boards plus the state election board. Unaffiliated is the largest category and they get none. So we’re talking about 505 potential slots and the largest category gets zero. So that would be one: put people on these boards that actually have some power over how elections are run.

Also, thinking through the signature requirements. Signature requirements right now make it very, very difficult to even get on the ballot in the first place, and even if we make it easier to get on the ballot, we have a whole set of structural issues that are really beyond the control of North Carolina, many of them that will likely stop most unaffiliated candidates, not named Arnold Schwarzenegger, from being elected.

Let’s say some of those hurdles were met and it became easier for unaffiliated candidates to run. Could that have an impact on increasing bipartisanship and compromise?

I think at the local level it could. The problem at the state level is that until they had some sort of a mass, they couldn’t get anything done policy wise. Everything in the General Assembly and in all state legislatures and legislative bodies, they break into caucuses or they start conversations and caucuses. So what we’ve seen with the very small number of unaffiliated people that have been elected to the General Assembly is almost as soon as they get in, they switch to a party. So it would be very difficult. At the local level it’s possible.

But— and this is maybe helpful for your readers as it’s something that I think has been undercovered: right now in a lot of our local governments, you don’t run by party. You can be unaffiliated, you can be Democrat, you can be Republican. And so we do see a lot of unaffiliated folks in those offices because there is no party label on the ballot. Well, the General Assembly in the last few years has been using local bills in really, really smart political ways, which is they’ve been changing local elections and counties from nonpartisan to partisan affairs. And if the Republicans are in control of more counties than the Democrats, you figure this will probably benefit the Republican Party, in this case Republican supermajority.

What’s interesting about these local bills is that they don’t go to the governor’s desk for veto. They get passed without ever seeing the desk. So the things that would clue a journalist to watch this bill, oftentimes it’s the Governor saying “I veto it,” right? That never happens and they tend to only affect a small number of places. So the statewide press probably are not going to pay attention to Madison County elections going from nonpartisan to partisan affairs, but then the reach of the Madison County press isn’t going to hit Raleigh to say maybe this is a problem and running counter to what the people in this place want. I think there’s kind of an immediate structural problem that makes this story a little undertold.

You have a great chapter about the information industry in NC politics, looking partially at lobbyists and there’s more than 730 of them representing nearly 1200 different groups or interests. In what ways do you think news and information orgs could help the public better understand these interests and the impact they have on policy?

I’ll try to give some answers and I’ll acknowledge at the beginning that I realize it’s hard. Readers don’t have space in their brain for who these lobbyists are. So if you start a story with Phil Berger, they clue in. If you start a story with Skye David, your average reader doesn’t, right? So I think trying to build the information architecture in readers’ heads over time is important.

In a lot of ways, there are some really good lobbyists, and there are people lobbying for causes we all care about: lobbying for open government and access for journalists, lobbying for me to have more places to mountain bike. So not all lobbyists are evil and just because I think they need to be covered more doesn’t mean that I think the coverage all needs to be negative. But I think this is the reality of how policy is made in this state and in every state, and we’re not always doing the best job covering them.

I’ll give you a good example: former Asheville Citizen Times and now Asheville Watchdog reporter Andrew Jones FOIA’d essentially a call for lobbyists from Buncombe County and covered what they were looking for in a lobbyist. That was incredibly valuable, I thought, as a service to the readers and as a reminder to the local government that there’s somebody there watching. I found it very helpful. Buncombe County is paying a lobbying firm more money than the combined salary of all the state legislators who represent Buncombe County. Yet of course, we’re spending a lot more of our time covering the legislators.

So what does that mean practically? Many journalists are doing this, but having the lobbying guide bookmarked. You can go through it at any time and look to see who are the principals and who are the lobbyists for all sorts of organizations so when a bill comes up like sports gambling that all of a sudden gets a lot of attention, maybe if not the first, the 2nd or 3rd or 4th stop should be the lobbying directory to figure out who has been working on that issue, how long have they been doing it and who’s paying them to do it?

That’s really helpful. So as we’ve seen recently, the Republican controlled legislature passes bills, the governor vetoes them, the supermajority overrides that veto. What did your research find about these weaknesses with the governor’s veto and why do you think that needs to be reformed?

We have the weakest governor in the country. In terms of institutional power, we were the last state in the country to give the governor the veto power, which is the primary tool they have. We are almost 100 years after every other state. It is designed to be weak. Then when we finally put in the veto, we gave the governor a pretty weak veto. So the governor cannot veto local bills, also constitutional amendments and also, and critically, redistricting. Just imagine for a second how different our state would be if the governor was able to veto redistricting maps like they are in many, many, many states. And to add a couple of more to the list of reasons why governors are not very powerful: when we gave the governor veto power we did not give them line item veto power. Forty-five states allow the governor to have some version of line item veto power. We’re one of five who do not. We also have this very diffuse power structure in the executive branch. We have the governor plus nine other offices, which is a very, very large Council of State.

In terms of the budget, the governor has essentially no power. So every time the governor first puts their budget out there, and then the General Assembly responds in their usual way, they way they respond is by bringing the Governor’s budget directly to the recycling bin. So it’s just not set up for very much power and I think that fundamentally changes everything about our government and it also means that the person who all of our eyes are on the most, Governor Cooper in this case, is the person with the least amount of power. The people who have the most amount of power are the ones that are hardest to find. It’s a real information problem.

You tackle some potential reforms at the end, including eliminating the literacy test, professionalizing the legislature, eliminating off year elections, an independent redistricting commission, which our neighbor to the north is working on. Which one of these would be best to tackle first and why?

I think the literacy test is the one to tackle first because it enters the conversation with the most bipartisan support. Nobody is going to publicly support a literacy test being in the state constitution, right? It’s got bipartisan backing and I think if there’s a proof of concept reform that we can have bipartisan solutions, I think that’s the one.

The hardest one is definitely the independent redistricting reform. I try to pierce the fiction in the book that it’s not possible. There are states that do this and that do it well, that does not mean that every state that does it does it well. But there are models that work and to me that one should happen somewhat soon because it’s not clear who’s necessarily going to have the most to lose in 2031, when we redraw these maps again. So the key to getting redistricting reform passed is to get it when both parties think that it might benefit them to pass it and the farther away we are from that timeline, I think the better off we’re going to be. It would be extremely difficult. I’m under no illusion that this is an easy lift, but I think other states have taught us it is a lift that is possible.

Additional resources:

“Anatomy of a Purple” is available for pre-order now and on bookshelves October 15th. The book includes an extremely helpful “Information Guide to North Carolina Politics” which includes books, research articles, local news outlets, podcasts, blogs and newsletters (including this one, thank you Chris!). Chris’s personal website includes a lot of valuable resources as well and is updated regularly.

We also wanted to highlight a few other recent interviews with Chris, including with WUNC’s Jeff Tiberii (who Chris shared in our interview is part of the origin story for his book), Spectrum News’s Tim Boyum, Triangle Blog Blog’s Julian Taylor and INDY’s Chase Pellegrini de Paur.

Correction: In the original version of this piece, we incorrectly spelled Jeff Tiberii’s last name. The Q&A has been updated.